Select a category

The Triforce of UX : Part III — Humility

Having conquered the big bosses Apathy and Indifference to obtain the Triforces of Empathy and Curiosity, at last, our hero faces the greatest force of destruction the world has ever known: Pride.

3 Qualities To Seek In Your Next UX Designer

Read Part I here. Read Part II here.

Having conquered the big bosses Apathy and Indifference to obtain the Triforces of Empathy and Curiosity, at last, our hero faces the greatest force of destruction the world has ever known: Pride. If our hero can overcome Pride to at last take hold of the Triforce of Humility, The Triforce of UX will be whole once more...

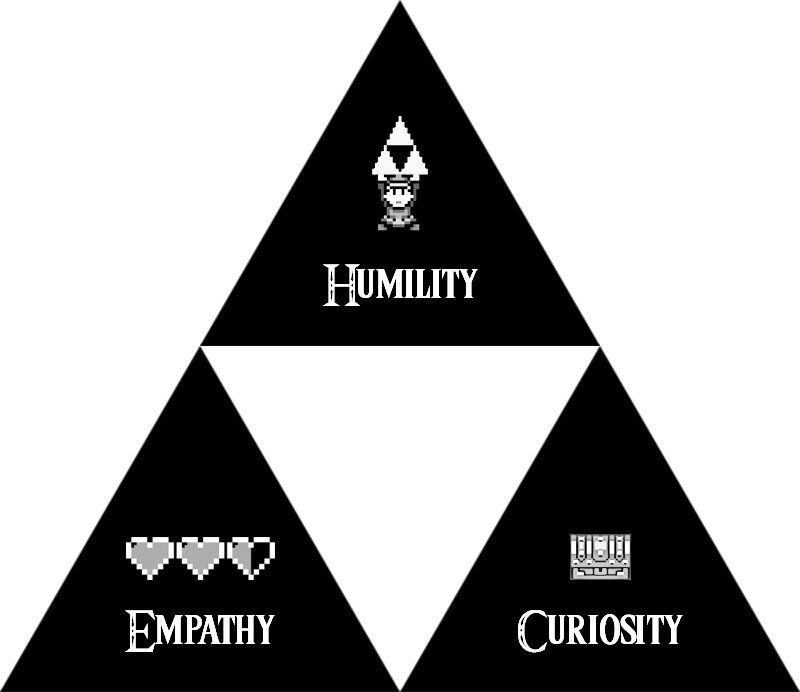

The Triforce of UX

The Triforce of UX consists of Empathy, Curiosity, and Humility.

In each part of this three-part series, I discuss why I believe each of these are the three most important aspects of a good UX Designer and three questions to ask to discover if the candidate matches these qualities. I’m sure many of you will disagree with me on some or all of these. That’s okay. I understand how you might feel. I’m curious to better understand why you feel that way, and would be humbled by your responses ;-)

PART III: The Triforce of Humility

The Triforce of Humility

In The Legend of Zelda, the evil Ganon seeks the Triforce in order to conquer, rule, and destroy. The underdog hero Link must fight incredible odds to defeat Ganon’s minions, find the pieces of the Triforce, and combine them in order to defeat the much-more-powerful foe. One of the things I love most about the Triforce is the fact that it can be wielded by both good and evil. It is a tool. Like most tools in our world, the things wrought thereby are reflections of the tool-holder, not the tool itself. Additionally, if the Triforce is wielded by one out of balance (i.e. prizing one of the pieces over the others) it will grant them some short-term power, then break itself apart and scatter once more.

If the heart of the one who holds the sacred triangle has all three forces in balance, that one will gain the True Force to govern all. But, if that one’s heart is not in balance, the Triforce will separate into three parts...

— Zelda, Ocarina of Time

Over time in the Zelda universe, many people good and evil have searched for the Triforce. But inevitably, most were tainted by the lust for the power promised by its possession.

…yearning for the Triforce soon turned to lust for power, which in turn led to the spilling of blood. Soon the only motive left among those searching for the Triforce was pure greed.

— Gates to the Golden Land

For this reason, in many of the Zelda storylines, Link decides to give up the Triforce once the enemy is defeated, lest he too becomes corrupted by the power he possesses, and become the very thing he fights against. This is why I posit the pinnacle piece of The Triforce of UX is Humility. The same is true in UX.

When considering a UX candidate, ask yourself some questions:

Does the candidate want to build up others, or themselves? Are they seeking to impose their will, or to establish balance in the team? Do they use their position as a weapon, or a binding agent?

Or, is this another hot shot MY Experience designer? (A UX Designer without the U is a MyX Designer). Is this person always right? Is it their way or the highway? How do they deal with criticism or critique? What happens when a junior developer tells them their design sucks and she found a better way? Humility in design isn’t new. Google it.

3 Humble Questions For Candidates

1. Tell me about a time when you were wrong. or — Tell me about a time when you failed.

I’ve been here. We all have. Sometimes we get it wrong. It sucks. What you’re looking for here is the introspection — the comprehension to know they’ve made a mistake and the courage to discuss it openly. Are they humble enough to admit they’ve made a mistake then take action to rectify it? As leaders we don’t want to be alpha-buffalo, our herds following blindly. You need to be able to trust each other and know that when things go awry you’ve built a team that will put out the fire then tell you about it, rather than call you in a panic asking what they should do. The ability to recognize one’s own mistakes is key in design. Only then are we able to subordinate our wills and desires for the greater good of the product.

Is this candidate humble enough to accept they’ve made a mistake? That they’re wrong? How will they react when you tell them they’ve messed up and need to redo all of their work? Are they able to see the wisdom in others’ opinions and self-introspect? Can they take criticism, learn from it, and use it as a tool for growth into something better than they were before?

Prototype like you know you’re right, test like you know you’re wrong.

There’s a saying based on a line by Robert I. Sutton to “Fight like you know you’re right, listen like you know you’re wrong.” I love it. I’ve heard it extended to UX Design thusly: “Prototype like you know you’re right, test like you know you’re wrong.” Surely there’s a healthy hubris in every designer. There has to be really. How else does someone look at something and say “I can do better than that!” or “Look at this thing I made! Isn’t it lovely!?” There is a lot of one’s self that gets imbued in the things we design — because we think or know we’re doing it right. But when it comes to testing a design with users, stakeholders, and ourselves, without humility the designer will be incapable of discerning what they did right from wrong. What is really working and what is really broken?

The struggle is real. Does this UX candidate have the humility to figure out how to help that user?

Every person you meet knows something you don’t.

— Bill Nye

Confidence is also incredibly important in a designer. They have to stand up in meetings, present, defend, and often fight for what they know is right. All of this requires a bit of pride in one’s work. However, like Zelda said if “…one’s heart is not in balance, the Triforce will separate into three parts…”. Without the balance of humility, a designer eventually stands alone and apart from the team. Empathy is supplanted by Apathy, and Curiosity by Indifference. Every person a designer interacts with has something to teach them. Humility is the key to helping a designer continue learning, and growing, even when they’ve done great things in the past. It’s also the key to binding their teammates together into an elite team capable of designing and building great things. It also takes great confidence to admit when you’re wrong.

2. A developer calls you over to their desk to show you how they implemented your design, but they’ve made some significant changes. What do you do?

If you’ve never been here, too bad. I’ve had the opportunity to work with some great developers. On more than one occasion I’ve had this exact experience. The first time it happened I thought “Oh great, the lazy dev didn’t want to take the time to execute my designs properly, now they’re going to ask me to sign off on their poor excuse for a UI.” In all honesty, sometimes that happens. But when you work with really great people often they’re about to blow your mind. I remember one such case where Jeff “Sharpie” Sharp called me over to his desk. “Now, I didn’t build this the way you designed it. Well actually I did and well, it sucked, so I did it this way instead and I want to show you why it’s better.” (I may be paraphrasing, but I’m pretty sure that’s what he said verbatim :-P) “Okaaaaayyyy…” I said. Then Sharpie proceeded to show me how, when actually implemented, what I’d designed, while valid in the prototype, didn’t function that way in the real world. After playing with it for a bit, he’d figured out a way to fix my design, and came up with a better approach. We walked through the InVision prototype I’d made, then through his approach. Sharpie’s was better. “Wow!” I said, “That’s way better. I like what you did. Let’s stick with that. I think the users will really appreciate that flow.” And we went on with our day.

Other times it went the other way, of course with fewer senior developers. (Sharpie has the good fortune of never being wrong). I might’ve responded with, “Well, I see why you’d think that. Honestly, that was one of the ways I’d originally solved the problem, but when we tested with users we found these problems with that approach. So I really need you to do it the way it was originally designed. It tested well and solves these other problems you hadn’t considered in these ways. But I really appreciate that you’re fighting for the user! It’s really important to me that you care about the UX of our product too.”

What you’re seeking in this question is how they react when people move their cheese. Do they freak out? Do they get defensive? Are they inextricably intertwined with their designs, unable to let go? Are they pushovers, bending at the whim of every critique? The latter is not humility, it’s subservience. You absolutely do not want a “Yes-Man” for a designer. There’s a big difference between admitting you’re wrong and cowing to everyone for fear of offense or antagonism.

True humility is not thinking less of yourself; it is thinking of yourself less.

— C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity

3. You know you’re right. You have the data and evidence to support your position, but the primary stakeholder just doesn’t like it and wants something else you know is wrong. What do you do?

I have yet to be on a project where everyone agrees about everything. How will this candidate take it when the lack of humility (or sometimes intelligence) in another will adversely affect the project? Is every hill worth dying for to them? Do they pick their battles? How do they decide what’s worth fighting for, and what’s not? Do they have the necessary skills to teach without being condescending? Can they lead from the shadows? How well do they function when the conversation goes crucial?

This is something I really struggle with. I’ve been on a project where the stakeholder insisted on a feature I was convinced was not just frivolous and ultimately not useful, but damaging to the project timeline. But I was so new at the time, I just rolled with it, and put up no resistance (can you say “yes-man?”). Team morale suffered because nobody wanted the feature. It took months to properly implement. I had developers I led who refused to touch it, outright unassigning themselves from related tasks, bugs, and stories. When we finally launched, it was a huge sales talking point. It helped sell the product like nothing else. That big increase in sales led to our acquisition. People made bank in part because of that silly feature nobody wanted. The stakeholder was right, I was wrong.

More painful though, is when ultimately, you were right, they were wrong, and the project suffered or failed because of it. How will they avoid this situation? How will they handle it when they’ve planted a flag on a hill to die for, fought the good fight, and ultimately lost? What happens next?

One of my previous clients and I had a large disagreement on the tone of the language in the application. After researching, studying, and testing competing and related products I felt we needed a light-hearted, warm/fuzzy approach to the language to contrast the cold, hard numbers of the accounting platform. Other products did it to great success. It matched what I know of HCI and could’ve been a great competitive advantage. We designed it. We demoed it. The CEO/Owner hated it. We educated. We held meetings. We preached. He listened. In the end, he still hated it, and wanted the language to be “professional.” We plead. We argued. The gavel fell, and the language was sanitized. I felt defeated. I felt like a failure. I took a step back and looked at the big picture. Interestingly, this was largely the only time in two years I’d failed to convince the client to do it my way. One hill in the mountain range of UX-wins we’d been able to get implemented. The product wouldn’t fail because its language was bland. The client would be okay. I would be okay. In retrospect, I should’ve acquiesced earlier, but my ego got in the way. I was used to the client just following my lead, and the one time our opinions differed, I got defensive. Humility is really, really hard. But this is how we learn, and ultimately grow from good designers to great.

The Triforce of UX

Looking back at our journey, I’m confident that if we can find designers who can effectively Empathize, are Curious to a fault, and Humble enough to know it we’ll be able to build amazing teams capable of innovative, and user-friendly products. Your UX designer is the hub of your product team. They must be willing and able to coexist and flourish among diverse personalities and contrasting, sometimes conflicting goals.

I hope you find value in applying The Triforce of UX when hiring your next UX designer. Might I also suggest we designers and leaders all seek to be a bit more empathetic, curious, and humble? I’d like to end this series with a quote from one of the great creative leaders of our time. I’ve substituted “designer” for “manager/leader”, as I believe his message is applicable to all:

I believe the best [designers] acknowledge and make room for what they do not know — not just because humility is a virtue but because until one adopts that mindset, the most striking breakthroughs cannot occur. I believe that [designers] must loosen the controls, not tighten them. They must accept risk; they must trust the people they work with and strive to clear the path for them; and always, they must pay attention to and engage with anything that creates fear. Moreover, successful [designers] embrace the reality that their models may be wrong or incomplete. Only when we admit what we don’t know can we ever hope to learn it.”

— Ed Catmull, Creativity, Inc.

The Triforce of UX : Part II — Curiosity

When last we saw our intrepid hero, he had unearthed the first foundational Triforce of UX: Empathy. Next, he must face the void in order to discover the next, but equally powerful Triforce of Curiosity.

3 Qualities To Seek In Your Next UX Designer

Read Part I here. Read Part III here.

When last we saw our intrepid hero, he had unearthed the first foundational Triforce of UX: Empathy. Next, he must face the void in order to discover the next, but equally powerful Triforce of Curiosity.

The Triforce of UX

The Triforce of UX consists of Empathy, Curiosity, and Humility.

In each part of this three-part series, I discuss why I believe each of these are the three most important aspects of a good UX Designer and three questions to ask to discover if the candidate matches these qualities. I’m sure many of you will disagree with me on some or all of these. That’s okay. I understand how you might feel. I’m curious to better understand why you feel that way, and would be humbled by your responses ;-)

PART II: The Triforce of Curiosity

The Triforce of Curiosity

In The Legend of Zelda, as in most games — nay, life! you begin with precious little. You acquire new relics, tools, weapons, and knowledge as you seek out and discover hidden treasures. Like a cheap box of crappy chocolates, you never know what’s inside! But unlike crappy chocolates, discovery of something new and strange is actually a good thing! The same is true in UX.

When considering a UX candidate, ask yourself some questions:

Does the candidate want to get into the heads, and hearts of the users/developers/stakeholders? Do they foster a healthy nature of inquiry? Do they harbor a desire to always be learning something new?

Or, is this another hot shot MY Experience designer? (A UX Designer without the U is a MyX Designer). Do they think their experience, knowledge, and anecdotal evidence will be “enough” to develop this project? Are you about to hire someone who thinks they’ve learned all they need to know and need go no further?

All artists are willing to suffer for their work. But why are so few prepared to learn to draw?

— Banksy

[embed]https://twitter.com/MrAlanCooper/status/714458052091445248[/embed]

When we think we know, we cease to learn.

— Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan

Without a deep-seated desire to empty our cups and fill them anew again and again we ossify; become stagnant knowers of history. You want to hire builders of the future. Because…

I think the other half is split between red and blue lasers

…and only half. The best designers provide the best solutions to the problem context. They can do this because they know what the actual problems are. They know the problems because they asked the right questions of the right people at the right times. They asked the right questions because they did their research. They researched because they were curious to find the actual problems. They were curious to find the actual problems because they wanted to find the best solutions. They wanted to find the best solutions because they felt empathy for the users. They sought empathy because they were humble, and were curious to see if there was something new to discover.

3 Curious Questions For Candidates

1. What inspires you?

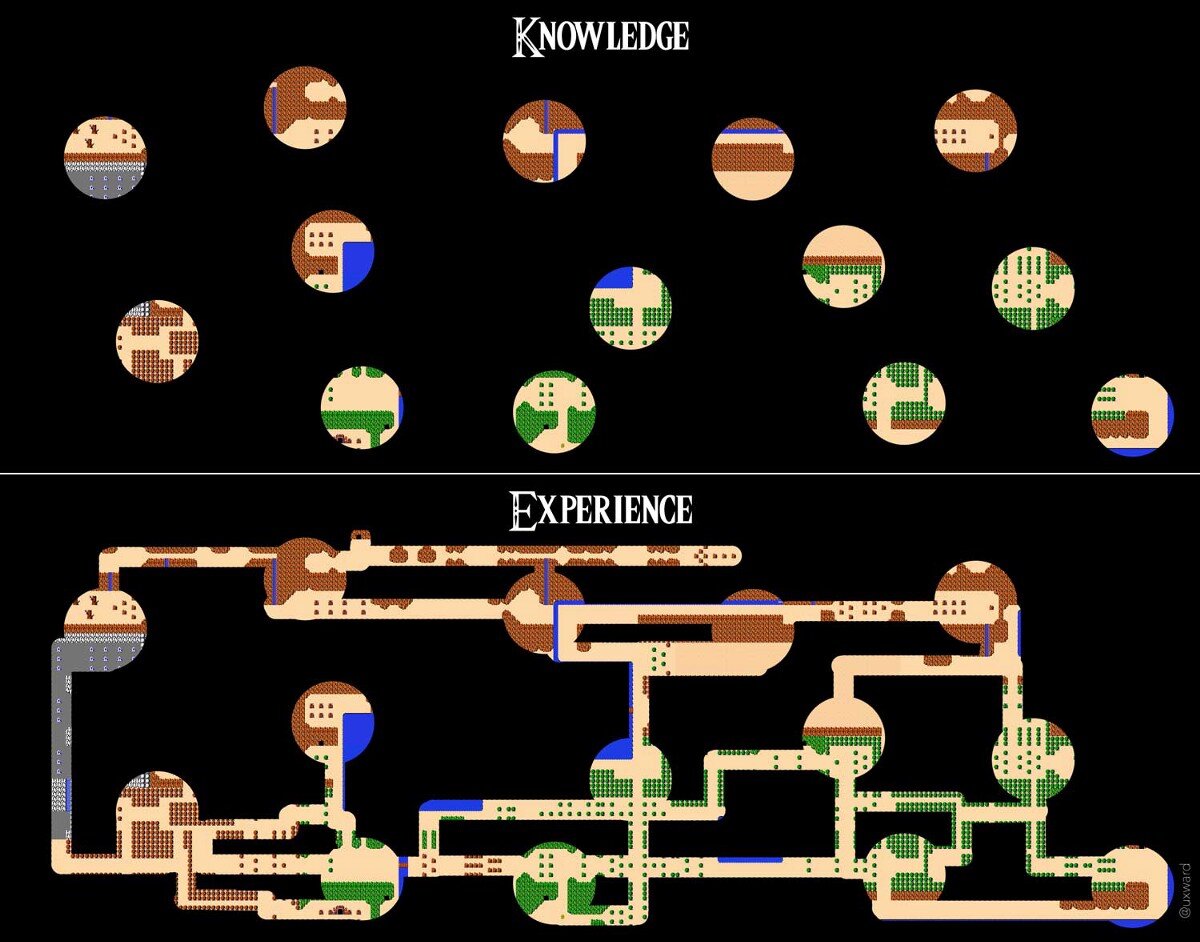

Nobody wants an uninspired designer. It’s kind of our core competency — to be inspired! Often we use the words inspired and creative interchangeably. “That was a creative solution! That design is inspired!” A lot of people think inspiration and creativity are always epiphanies or original inventions. Sometimes that’s true…maybe. But the bulk of inspiration comes from the intuitive connection of disparate thoughts, ideas, images, and patterns. You acquire the bits of information as knowledge. Your experience helps you connect those bits of information.

Riffing off a great visual by Hugh MacLeod

These connections help us better understand how our world is put together. They also give us insights into how we might solve a problem in a way that’s never been done before. But in my experience, more often than not, inspiration has come when I’ve discovered that the super-complex problem I’ve been looking at has already been solved incredibly well (sometimes by me in the same project), I just couldn’t see before that the problems were related or the same. At that point, you feel a bit silly — it all seems so clear, so obvious. But this is hindsight bias, and what really just happened was inspiration!

Creativity is just connecting things. When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel a little guilty because they didn’t really do it, they just saw something. It seemed obvious to them after a while. That’s because they were able to connect experiences they’ve had and synthesize new things. And the reason they were able to do that was that they’ve had more experiences or they have thought more about their experiences than other people. Unfortunately, that’s too rare a commodity. A lot of people in our industry haven’t had very diverse experiences. So they don’t have enough dots to connect, and they end up with very linear solutions without a broad perspective on the problem. The broader one’s understanding of the human experience, the better design we will have.

— Steve Jobs, WIRED, February, 1996

When you ask your candidates about what inspires them, you’re delving into their knowledge and knowledge-mapping experience. How deep is their well of experiences? How diverse? Are they a spread-thin generalist — a mile wide and an inch deep? Are they laser-focused specialists — an inch wide and a mile deep? Are they something in between? You might want one, or both, or a hybrid. That all depends on you, your project, and your team. Ask follow-up questions about the breadth and depth of their knowledge and experiences.

Use their résumé, portfolio, website, Twitter bio, LinkedIn recommendations, whatever you have, to guide you to probing questions regarding past experiences, and projects. How did they gain the knowledge they have? What urges them onward to acquire new knowledge? How have they applied seemingly unrelated bits of knowledge in meaningful ways? Can they connect the dots?

“Wait, wait, wait!” you say! “Brandon: first you basically inferred that a designer relying on their knowledge and experience was a bad thing! Now you’re saying that’s where inspiration comes from!? Which is it?”

Old knowledge is helpful, but new knowledge will be the key that unlocks the best solutions for new problems.

Great question! I’m glad you asked. The difference is really about context. In the Steve Jobs quote above he said “…a lot of [designers] haven’t had very diverse experiences.” and therefore “…they end up with very linear solutions.” I interpret his remarks to mean not that they aren’t knowledgeable, but that the scope of their knowledge leads them to rote, banal, or possibly incorrect solutions. By doing new research, new reading, and new learning, (you could also substitute new for different) we diversify and gain knowledge about the current problem in its current context with the current user base. Old knowledge is helpful, but new knowledge will be the key that unlocks the best solutions for new problems.

Microbot from Big Hero 6

This clip from Big Hero 6 is the perfect example. Remember that Callaghan invented the tech for Hiro’s battle bot. Hiro had already invented his battle bot leveraging that tech. All Hiro needed was a “new angle” to be able to see another, radical application of that same idea — the microbot. (If you haven’t seen BH6, you should. It’s awesome. Thanks to my two-year-old and five-year-old, I’ve seen it probably 50 times, and still like it)

2. Are you involved with online/local/national/global UX communities? In what ways?

Depending on where your company is based geographically, and the candidate’s personality type, they may only have interacted with other UX designers via books, forums, or websites. That’s okay. What you’re trying to determine is if this candidate operates in a vacuum or if they seek new learning and insights from their peers, mentors, and industry leaders. The medium isn’t as important as their involvement.

Storytime!

UX has been around for a very long time. Much longer than you might think. There is no shortage of available information on the subject. But that didn’t keep me from not knowing anything about it! I was one of those earnest seekers of knowledge only kept from the truth because I knew not where to find it. I first learned of the terms Interaction and User Experience design from a recruiter. She cold-called me and said I was perfect for a lead UX role at a hot startup in Seattle. Delightful! But I was a bit befuddled — how could I be qualified for a role let alone a Lead role if I’d never heard of that role? She’d read my LinkedIn profile and surmised that based on my experience with various technologies and roles I’d be a good fit for a UX position. She was right! I researched the field, discovered that this weird hybrid dev-igner I’d been trying to be for the last 7 years was actually a legitimate field. I took the job. Then I got to learning! I read The Inmates are Running The Asylum, About Face, The Design of Everyday Things, Don’t Make Me Think, and Rocket Surgery Made Easy. I immersed myself in the field’s literature determined to hone my skills.

These books (and many more) are only one way to be involved in the community. I didn’t know it at the time but there were local, national, and global conferences dedicated to helping people like me grow. As I learned of each event I found new ways to rekindle my curiosity, learn, grow, and be inspired by my peers and mentors.

When the student is ready, the teacher will appear.

Speaking of mentors…does the candidate have one? More than one? Who are they? How often do they meet, and what do they discuss? If they don’t have at least one, why not? What are their career aspirations? (This will help you determine how hungry they are for knowledge and industry participation outside of their day-to-day, in addition to their drive and motivations.) Do they attend meetups? Which ones? When was the last one? What did they learn? Do they ever speak at these events? Are they finding ways to get involved? (Additionally — ask yourself if you’re providing the means and motivation in your own company to encourage your people to learn, grow, and get involved).

A lot of the public, large-group stuff (conferences, meetups, happy-hours) can be intimidating or just flat-out a non-starter with some personalities. Don’t let that sway you. There are numerous, individual ways people can be involved — writing blogs and articles, discussing ideas on IxDA and Stack Overflow, or like me when I first started — reading. Your goal here is to discover not just how they’re engaging with the community, but that they’re engaging. Your endgame is to discern how and when they learn, or if they seek learning and growth at all.

3. When was the last time you learned something new? What was it? Who/what taught you? How did it change you?

This last question is pretty straightforward. Are they continuously and consciously learning? Are they the eyes-wide-open, fresh-off-the-boat, giddy-as-a-school-kid, voraciously curious type? Are they the staunch, know-it-all, set-in-their-ways, tenured professor type? Did they read something this morning that got them thinking about something at work in a new way? Was it so long ago that the knowledge is now old-hat or irrelevant? What changes did they make in their habits/life/practice/thought-processes based on this new knowledge?

A fool uttereth all his mind: but a wise man keepeth it in till afterwards.

— Proverbs 29:11

Give them a few minutes to formulate a response. Since we don’t have parents cornering us at the dinner table every night asking “So, what did you learn today, hmmmm?” it’s not one of those things we tend to think about regularly. Additionally for some, learning and being curious about the world around them may be so second-nature that they don’t even think of it as anything relevant. They just do it. Give them a chance to introspect. The ability to respond quickly, thinking on one’s feet is important, but so is the ability to stop, and really dig deep (see Proverb above). As an interviewee I’ve appreciated the times when the interviewer set the bar by saying things like “take your time” and “it’s okay to think about this for a minute or so — I really want your best answer here”. I’ve even had an interviewer say “Take the next two minutes to think about my next question, then respond.” This meaningful break can give you both an opportunity to stop and take a breath — to connect to the deeper thoughts and memories without the pressure of an immediate response. If the candidate seems uncomfortable with the silence, you can even excuse yourself for a bit “I’m going to step out for a minute or so while you collect your thoughts — would you like some water?”

You can also use this as an opportunity to see how the candidate formulates deeper, more complex ideas. In effect, you’re asking them to connect the dots on their experiences to lead to a creative insight for this interview question. You’re probing for inspiration! Given the additional time allowed, you’re looking for something deeper than their patent responses. Did they use the time to formulate something meaningful? Did they delve deeper and discover something, perhaps even new to them on the spot? Did they learn anything from this experience?

I hope you’ve enjoyed Part II of our foray into the Triforce of UX. Stay tuned for Part III: The Triforce of Humility. Please comment, and respond! I’m really curious how the community feels about the questions I chose and why. Do you have any that are better? Please share!

What separates the good designers from the great?

The Triforce of UX : Part I — Empathy

In each part of this three-part series, I discuss why I believe empathy, curiosity, and humility are the three most important aspects of a good UX Designer, and three questions to ask to discover if the candidate matches these qualities.

3 Qualities To Seek In Your Next UX Designer

The Triforce

Preface

After 2 awesome years with Improving, I took a leap of faith and joined Precocity. Leaving my former employer also meant leaving my client. It was one of those rare golden client/consultant relationships; it felt like we’d worked together for ages and were always on the same wavelength. Upon my departure, the client wanted to hire an in-house user experience (UX) designer that could meet or exceed the relationship we’d had. They contacted me and asked 2 key questions:

What three skills would you place as most important for a UX Designer?

How you might phrase some interview questions to validate a candidate actually has those skills?

Having both interviewed and been interviewed for UX positions many, many times over the years I must shamefully concede that I’d never actually asked myself those questions. As I began to answer those questions (now more for myself than the client) I realized I had incredibly strong opinions on this subject. Then as I began to compile my thoughts a friend of mine asked me the exact same questions but from the candidate’s point of view. Thus this 3 part series was born.

The Triforce

What geek worth their salt can be asked to codify anything in 3 parts and not liken it to The Triforce?

The Triforce is one of the most iconic symbols in video game lore. In Nintendo’s The Legend of Zelda, it’s an omnipotent sacred relic. Each triangle represents a Triforce all of which make up The Triforce when combined. In the game, they represent Power, Wisdom, and Courage.

While admirable all, in answer to my client and friend I believe The Triforce of UX consists of Empathy, Curiosity, and Humility.

The Triforce of UX

In each part of this three-part series, I discuss why I believe each of these are the three most important aspects of a good UX Designer and three questions to ask to discover if the candidate matches these qualities. I’m sure many of you will disagree with me on some or all of these. That’s okay. I understand how you might feel. I’m curious to better understand why you feel that way, and would be humbled by your responses ;-)

Read Part II here. Read Part III here.

PART I: The Triforce of Empathy

The Triforce of Empathy

In The Legend of Zelda, your health is measured in little hearts. The more hearts you have the more health you have, the stronger you are, the longer you’ll live, the longer you’ll last in battle. The same is true in UX.

When considering a UX candidate, ask yourself some questions:

Does the candidate know how to get into the heads, and hearts of the users/developers/stakeholders? Can they walk a mile in their shoes?

Or, is this some hot-shot MY Experience designer? (A UX Designer without the U is a MyX Designer). Do they think the answers to all of their questions lie in their own background, knowledge, and experience? Do they cloister themselves atop Mount Sinai then descend bearing the stone mockups from on high with God’s Gift to Software®, or are they sitting at the feet of the people who will actually use the software, studying them? Are they trying to discern what the users’ and business’ problems are, and how the customers might more easily accomplish their goals?

This is what I mean by empathy. It’s also not just for the users. The best designers are good negotiators, mediators, and bridge-builders. If each member of the business, development, and user pool are the spokes of a wheel, the UX designer is the hub around which these things turn. They bind disparate parts into a functional whole with a centered and unified focus. They don’t make enemies, they make allies. They build relationships of trust and accountability. Everyone needs to be able to trust the UX designer, and feel free and encouraged to come to them with the gnarliest of their problems.

When designing solutions the best UX designers will be juggling all of the research and notes from all of those involved trying to come up with the solution that fits the customer first then all others accordingly.

3 Empathy Questions For Candidates

1. What’s your primary goal as a UX Designer?

After all the chit-chat, ice-breaking, and weather talk, open here. We want to discover if this candidate’s mental model of UX aligns with yours. Their answer to this question (and how quickly they respond) could help save both of you an hour wasted. If you don’t sync here there’s not much reason to continue the conversation.

The answer I’m looking for speaks to making people rock stars at their jobs/tasks/etc. while balancing the needs of the business, and the realities of the humans involved in the process of making it. I want to know that they’re as passionate about creating amazing experiences for humans as I am. Basically, do our UX visions align at the macro level?

Listen for the order they rank items as they sift through their responses. They may never have voiced this verbally so give them some time to collect their thoughts and the freedom to rearrange. They might first mention developers and last the users; get them to clearly rank-order their responses after the fact.

In terms of importance, for me, they need to first focus on the end-users. It is after all the U in UX.

Next, do they care about shipping the product the client or business actually wants? Can they speak to helping the business steer clear of pitfalls and mistakes using their expertise and position to guide the business to the best possible version of their vision?

Lastly, but never least, do they care about the humans that will actually build it? Are they cognizant they may be asking people to give up time with their families and friends to build some lofty, impossible dream requiring new chip architectures and improbable bandwidth speeds in 6 months? Good designers understand that although the customer and business may want a thing, even need it, every feature we add, every interaction we invent means a developer’s time to implement — usually a lot more time than it took us to dream it up. We should never be anxious to volunteer other people’s time.

2. Tell me about your user-research techniques and methodologies.

What A UX Designer Actually Does

Here we’re starting to delve into soft skills. Can they talk to other humans? Is he meek as a mouse? Is she a blustering braggard? Neither is optimal. Even if you have separated your UX Research role from your UX Designer role, they still need to have a broad overlap of soft skills.

The very conversation you’re having will help you suss out much of their natural abilities. But to be a good researcher they should also have a conscious, purposeful method. Candidates need to be able to talk about interviewing people over the phone and in person. Are they able to help customers talk about their problems without leading them (open-ended vs close-ended questions)? Most importantly — are they capable of shadowing people in their own environments, seeing what their needs are and how and where they do their job? Do they even have a desire to do this and do they know why it’s so important? Are they able to mention these items free of prompting from you and can they eloquently articulate them?

Find out when they do research. How prominent a role does it play in their process? Is it an after-the-fact A/B test kind of thing? Do they like focus groups (and if so, dear Ganon WHY!?) Is this where they start or end? Is this iterative?

Ultimately the ability to accurately assess users’ needs will be the primary dictator as to whether the product solves anybody’s actual problems.

3. Who has final say what a UI looks like, and why?

This is a tough one. I know that my answer to this question has cost me at least 1 job. But it was actually a good thing — because the would-be employer’s opinion was fundamentally different from mine, and would’ve been a major source of contention. Fair warning: here be monsters.

UIs are designed by those who commit code.

IMNSHO the correct answer here is the developer; this is the answer I look for. Why? Because so much of what a designer does is consensus-building, and human coordination, it is vital that the UX designer, the hub of all these human interactions, recognize where true power lies: to extend the wheel metaphor, where the rubber meets the road. My friend Tim Rayburn told me once “Decisions are made by those who show up.” Let me be bold then and say similarly “UIs are designed by those who commit code.” When all was said and done your Sketch file went into the garbage, but code was shipped; that’s what the user sees and interacts with. All the rest of us make suggestions (functional specs, business requirements documents, flow charts, user stories, wireframes, prototypes, hi-fi mockups)— but ultimately those writing and committing are making the final call. The crux of it is this: When the designer builds a relationship of trust and accountability with developers everyone’s jobs become exponentially easier. And better. Another way to put this as Tim is wont to say

The .PSD is a lie.

“But Brandon,” you say “we have peer reviews, QA, UAT, checkpoints, sprint reviews, and…”. That’s all great I say. If you guys love it — keep it going. Self-managing, self-correcting teams should create processes of checks and balances that work for them. I prefer to trust my team to execute well and look to me for confirmation rather than approval. In that landscape, those same processes only work better.

[embed]https://twitter.com/diaryofscrum/status/469202961839968257[/embed]

Some might say stakeholders (business, CEOs, POs, etc.) own the final UI look and feel because they write the checks, are in charge of hiring/firing, etc. I’ve heard designers and CEOs alike say things like “They better implement what was designed or they’ll be out of a job!” Really? Where’s the trust? Where’s the empathy? Where’s the respect? Nobody wants to work for or with that person. Don’t be her; don’t hire him. The opposite is just as bad — we shouldn’t bow and bend to the whim of every architect. Many developers feel their sole duty is to say no every time new or changing work is presented. This is an okay checks and balances approach on the surface, but this too lacks trust, empathy, and respect. Nobody wants to work with that person either.

Remember — your UX designer is the hub of interaction for the business, design, and development. If the hub of the wheel doesn’t work well, the whole wheel fails.

I hope you’ve enjoyed Part I of our foray into the Triforce of UX. Stay tuned for Part II: The Triforce of Curiosity. Did I miss anything? Did I not pick your 3 favorites?

What would you say are the 3 most important aspects of a great UX designer?